The Christian Canon - pt 1

2014-05-20

I thought I’d write briefly on the canon of Scripture, but, as it is with everything I do and say, it ended up being not so brief.

Lately, I’ve been drawn to reading the Scriptures much more in depth than I have in almost a decade. So I decided to listen to Ancient Faith Radio’s Search the Scriptures and I’ve taken up another round of study over Genesis (which has been an obsession for me, & namely the creation narratives).

Dr. Jeannie Constantinou really got me thinking about the canon in her podcast (which I strongly recommend). Allow me to preface by saying that it is in no way my intent to downplay the role of the Bible; you only need to attend one Orthodox service, any service, to see the importance of the Bible in our Tradition is beyond obvious. Also, this is my personal work and I do not claim to speak as an authority on Orthodoxy here, in any blog entry, or anywhere else. With that in mind, here goes.

Growing up I remember hearing (and saying) things like, “All I need is Jesus and my Bible. Sola Scriptura was so engrained in my belief system that anything else seemed ludicrous; I mean, that’s how it was for the early Christians… right?

Looking back, I guess I subconsciously thought once each Gospel, Epistle, Acts, and Revelation were written, they were immediately copied and given to every Church who placed a copy in the hands of all of the faithful and they took their Bibles to church, sat in pews, had some praise and worship, then listened to a sermon and they were out. I hadn’t really thought this out too well, but instead just took at face value what I had known. The liturgical life of the early Church will be yet another topic for yet another day, but, for now, back to the canon.

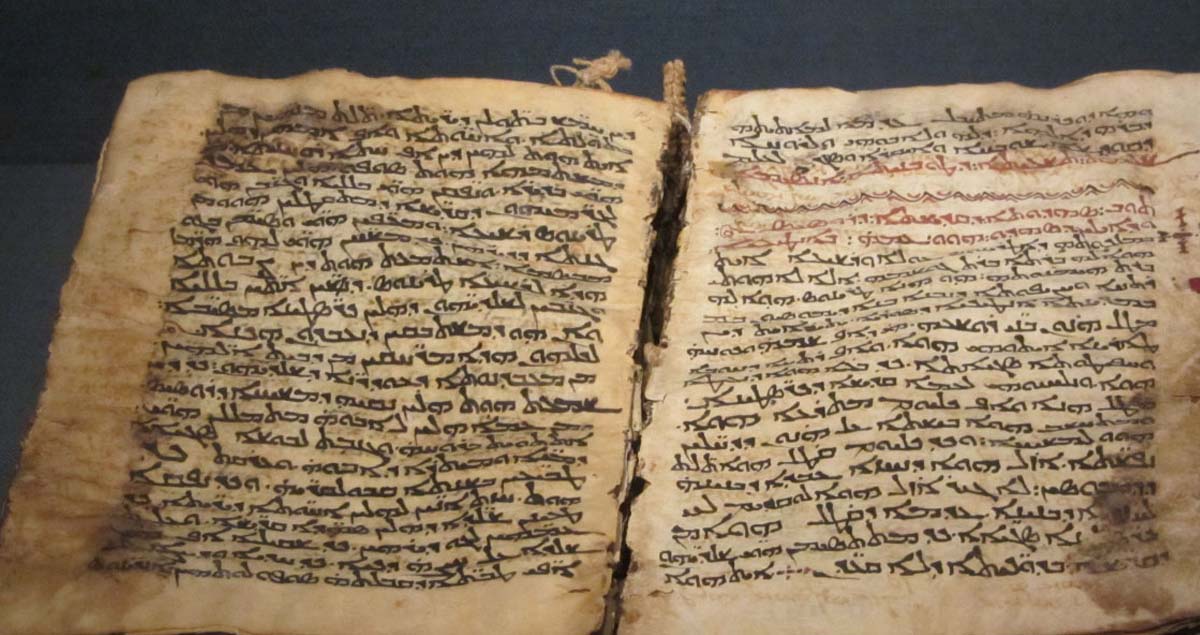

The dating of the books of the New Testament is not something there is a strong consensus on, but the earliest estimates are that the books were begun around 40 AD and completed at the end of the 1st century (90-100AD). Even after they were written, it is impossible to think every church received every book and, even the books the various churches had, were not immediately valued as on the same level as scripture as the Old Testament books. There is of course evidence that the writings of the Apostles were soon received as inspired; for example, St. Justin Martyr’s first apology discusses the “memoirs of the Apostles” (the Gospels) being read in the Churches along with the Old Testament as early as the end of the first century.

The early church really did not see a need to dogmatize the writings of the Apostles into a canon and, as an aside, the first proposal for a canon came from the heretical teacher Marcion in the mid to late second century.

Marcion was born in Sinope and made his way to Rome where he began teaching that the Christian God and the God of the Jews (the God of the Old Testament) were, in fact, incompatible and thus not the same, but instead were two separate gods. As a result, Marcion rejected the Old Testament completely , since that was the other God, and sought to make a Gospel that followed his theological perspective. He only accepted the Gospel of Luke as authoritative (even though he edited out everything that related to the Old Testament) and 11 of the letters of St. Paul. From everything I’ve studied, this is the first attempt to form a canon of the New Testament. Despite the obvious heresy and the intent of Marcion (who set up a church hierarchy for his followers alongside the Christian hierarchy as what he believed to be the true Christianity), Marcion began a discussion about the canon.

St. Irenaeus of Lyons, an early Church Father and apologist, argued for the use of Four Gospels. For St. Irenaeus, the four Gospels made up a tetramorph, which literally means symbolic arrangement of four elements, illustrating a canon of the Gospels that existed by the tradition of the Church. For St. Irenaeus, the idea of the four Gospels was logical when he writes:

The Gospels could not possibly be either more or less in number than they are. Since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is spread over all the earth, and the pillar and foundation of the Church is the gospel, and the Spirit of life, it fittingly has four pillars, everywhere breathing out incorruption and revivifying men…For the cherubim have four faces, and their faces are images of the activity of the Son of God. For the first living creature, it says, was like a lion, signifying his active and princely and royal character; the second was like an ox, showing his sacrificial and priestly order; the third had the face of a man, indicating very clearly his coming in human guise; and the fourth was like a flying eagle, making plain the giving of the Spirit who broods over the Church. Now the Gospels, in which Christ is enthroned, are like these.

This is where the idea of the connection to Matthew and the angel, Mark and the lion, Luke and the ox, and John to the eagle comes from.

This entry is long enough, I think, so I’m changing the title of it to The Christian Canon, pt 1 and will continue next week.